Executive Summary: QE and Inflation

- The mechanics of QE: how, when, who.

- The multiple objectives it seeks and achieves.

- The incentive structure it creates.

- Its relationship with inflation.

- The Fed, and why to incorporate interest rate futures into daily trading.

- Intermarket, as always leading the way.

- Intra-market, a perspective on how all sectors are doing relative to each other.

QE and inflation. A popular debate with no real substance

The Fed announced that it started buying bonds again, restarting what everyone knows as QE, or quantitative easing. Predictably, the debate kicked off across the media—especially in outlets focused on economics and finance.In general, the discussion centers on whether it’s inflationary or not. The reality is that QE is a powerful monetary policy tool that very few people actually understand how it works.

QE — how it works and what it’s trying to achieve, in street language.

- J.P. announces they’re going to buy bonds and pay for them with bank reserves.

- Banks with a direct line to the Fed bring the bonds in.

- The Fed hits enter (literally), and reserves show up credited in the bank’s account at the Fed—the equivalent of the bond that was delivered.

Have you ever taken out a bank loan? How does that work?

Some paperwork, maybe a meeting, and suddenly you log into home banking and your account is at crazy levels. The credit was approved and credited. QE is exactly the same. What we need to understand is the second-round effects of that action.

QE and Inflation: Up to this point, is this inflationary?

- The bank will only lend that new money if it sees potential profit in doing it and if there’s real demand for money—someone is actually asking for it. The inflationary fire shows up when money is created with no real demand behind it. But let’s go slowly, that topic goes beyond the scope of this article.

What do we achieve with this simple operation?

- A life insurance for the banks: Any liquidity situation the bank might have it´s gone. These liquidity squeezes usually happen in crisis situations, when panic spreads broadly. Runs on Banks ended, so to speak. This point is not minor at all, and it generally goes unnoticed.

- Does this higher level of reserves fix something in the real economy? We’ve already seen here that the answer is no. A broken business model that loses money doesn’t get fixed by throwing more money on top of it. No real changes in the real economy. Another point that usually goes unnoticed.

So where do the Fed and the bank stand after the transaction?

By buying these bonds with reserves, a one step process, all of these things are being generated at the same time:

On the Fed’s side

- The Fed buys them → there’s more demand for those bonds → that, by itself, helps with rates. A new, large buyer of bonds shows up. Not a minor point, especially in long end curve bonds, where demand is, and will get, more softer. We could also say it aims to control the yield curve, and we wouldn’t be lying. It helps with that too.

- Just like in the micro world, the bank gets paid a rate for parking reserves there. The Fed pays a minimal interest rate on those reserves. This is the key.

This is where the “magic” happens.

- That minimal interest the Fed pays to the banks, for the reserves the banks received in exchange for bonds, is lower than what the bank was earning by holding the bonds.

- In other words, the bank earned more by holding the bonds. They paid better.

- On a massive scale, that small difference in rates is a lot of money.

What’s the bank’s obvious reaction?

- The bank is going to turn around and swap those reserves for bonds.

- Bonds pay more and the Fed knows and wants this.

Habra cadabra.

- Another buyer of bonds appears. The Fed creates the incentive structure so banks want to buy those bonds.

- Post-2008, there’s an endless list of regulations that limit banks’ investment options. Treasuries, of course, have no such constraints—and the Fed takes them at par.

- Put yourself in the bank’s shoes. You’re sitting on reserves that pay almost nothing and you’re allowed to buy bonds that pay more. That alone is enough. But it gets even better.

- By buying a Treasury bond, that bond is backed by the Treasury. The reserves you were holding weren’t backed by anyone—other than the bank itself. In other words, you get paid more, and now you have someone to claim against if you don’t get paid. And that “someone” is the Treasury, which can print dollars—so your counterparty risk basically disappears.

QE and inflation: Why does all of this matter, and what does it have to do with inflation?

Bonds exist to finance the historically unprecedented fiscal deficit we’re living through. QE, among other things, creates incentives to buy those bonds—which is the same as financing the deficit.

A fiscal deficit is inventing money out of thin air—creating it because it simply isn’t there. This is one of the mechanisms that generates inflationary pressure. It’s not the only one, but it’s by far the most powerful, and it has been for quite some time.

Let’s review the achievements

- The Fed itself becomes a buyer of bonds—this, by itself, helps keep rates contained.

- It provides infinite liquidity to banks. Life insurance in reality.

- It creates an incentive system so private players also buy that bond. In other words, it creates more demand for the instrument that finances the fiscal deficit.

The banks

- They get a life insurance policy.They should never have liquidity problems again.

- In exchange, they enter a loop where they permanently have to buy these bonds, which finance the deficit. In a free-market situation, the bank probably wouldn’t eternally buy the debt of an economic agent that only keeps expanding its debt. Oracle could be a present-day example.

A fiscal-deficit financing loop is created. This does generate inflation. Demand for bonds gets created, rates stay the same or fall, and the wheel keeps turning.

Just imagine what would happen if these bonds ran out of demand. Nobody wants them?

Rates would rise enough to find buyers. That removes any control over rates. That’s risky in a system built on constant credit creation.

End the debate

So when they ask you whether QE is inflationary or not, the correct answer is: QE creates the incentives to buy the bonds that finance the deficit.

QE is not inflationary by itself. The deficit is.

Economic implications

A real economy built on a massive deficit, with QE behind it, is like a racehorse running on steroids.

This hits every sector of the economy (the S&P 500 today, house prices, car prices, food, everything ), but the likely victim in the long run is the dollar.

The reality with the dollar is not that it’s a strong currency. It’s a disaster if you look at the purchasing power it has lost—for example, versus gold.

The best way to measure the damage being done to the currency—and to the wealth of everyone who saves in it—is to look at the dollar versus gold. That’s where you really wake up.

The comparison isn’t against the euro, the yen, or the yuan. It’s against gold, home prices, and so on.

The other point from yesterday.

The Fed cut rates and it looked like a surprise. In practice, we already knew it for almost two weeks. (Basically, it’s when markets decide for the Fed through the interest-rate futures market.)

If we already knew it, why was yesterday important?

To read the Fed’s stance

Nothing is as efficient as waiting one day and looking at the futures market. That’s the market’s opinion—and at the end of the day, it’s the only one that matters.

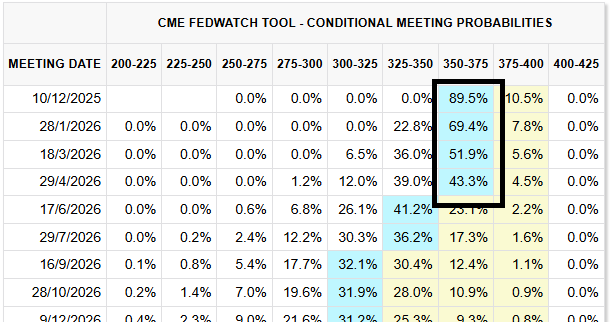

Thirty minutes before the Fed

This was the path of rate cuts the market was pricing going forward.

At the next meeting, on January 28, as you can see in the left-hand column, the market was pricing in a cut with 69.4% “certainty.” Notice that going into the meeting, the market was already assigning an 89.5% probability to that cut.

It had already priced in almost everything—and it had been doing so for the past two weeks, as we’ve shown here. In other words, up until yesterday, the market believed—with 69.4% certainty—that another cut was coming on January 28.

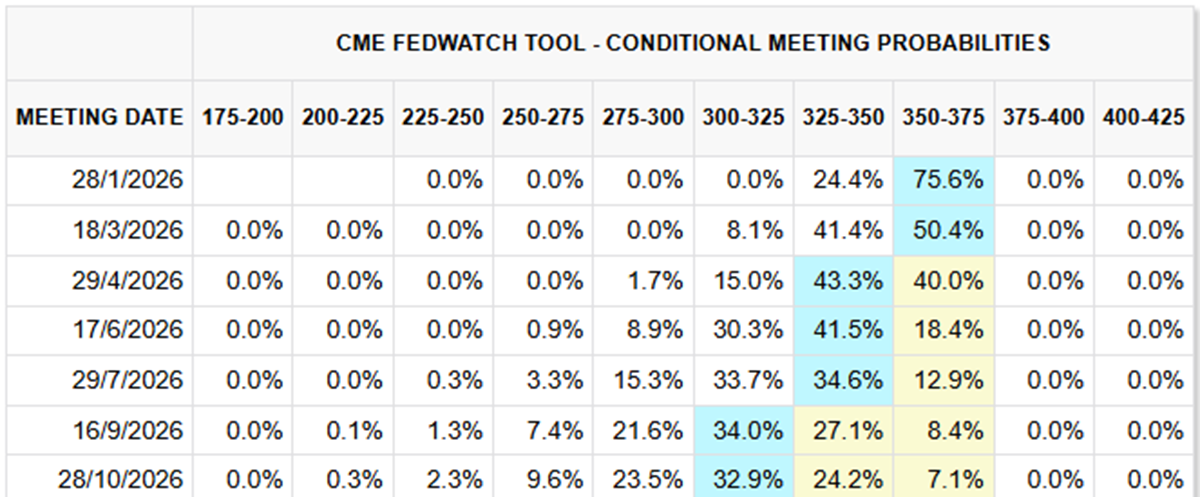

Today…

Post-cut—now Thursday the 11th—look at the probability for January 28. The market is now assigning a 75.6% probability to a cut on January 28. So far, it read the Fed as a bit more hawkish than it did yesterday. That’s the correct interpretation of what happened yesterday.

What comes next?

Of course, as new information reaches the market, these probabilities will change. What matters is knowing where the market is positioned, because that’s how we can try to anticipate reactions—what data has more or less potential to generate volatility, and so on.

For example:

Let’s assume a disastrous jobs report—the one coming out in a few days. Does it have the potential to create volatility?

It’s harder. If the market is already pricing a cut with roughly 75% odds, it’s already leaning in that direction.

A much stronger catalyst for volatility would be an excellent jobs report. Then the cut probability would have to adjust to a new reality that is not currently in the price.

It’s this trade-off—between the probabilities already priced in and the incoming news—that creates situations like:

Good macro news, markets fall.

Bad macro news, markets rise.

Intermarkets always shows the road ahead

Why would this trend stop? For now, I don’t see why it would.

Intra Market

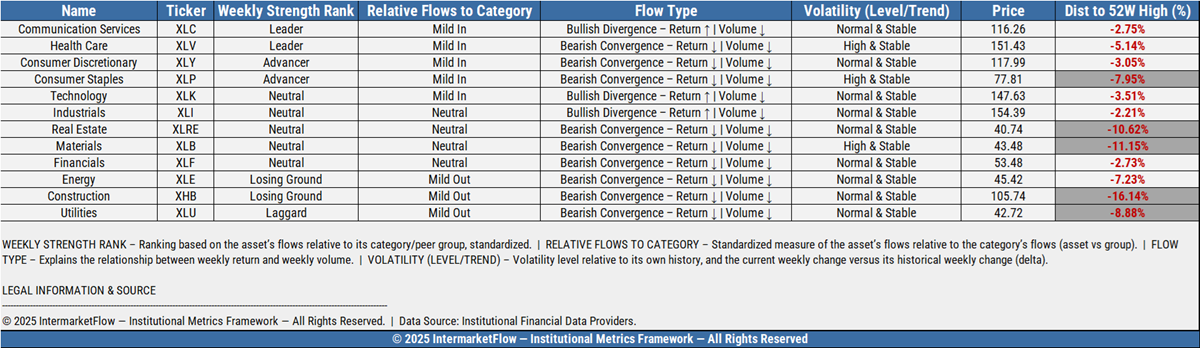

Before wrapping up, I wanted to show this table we use to track the weekly rotation across sectors. That’s not the relevant point today—I just want you to focus on the last column.

It shows the percentage distance each sector is from its 52-week high. In reality, it would be its all-time high. Most sectors are basically right there, but when you look at the ones that are farther away, you can see which sectors are actually suffering—yet still sitting just a step away from their all-time highs.

See you midweek report

Martin

If you believe this is an error, please contact the administrator.